Long post – 8-10 minutes read

Potential Connection Two: Reconsidering the lines (of control) around concepts.

This is the third in a series of blogs in which I record seemingly random and unconnected thoughts which relate to contemporary art and “But a child could do that!” responses. It is much longer than the previous and again, does not promise resolution. Recall, that it was Iain McGilchrist’s comments about contemporary art at the end of his book The Master and his Emissary: the Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (2019) that sent me on this rambling investigation, when he wrote that future generations might look back on our era and wonder why we were so gullible to think certain contemporary art had anything valuable to offer. It is not really McGilchrist I am picking on, but a developing inquiry around the glaring obviousness of our material selves in a material world, and an emerging *”negative messianism”.

On one hand, he writes “The left hemisphere’s world is ultimately narcissistic, in the sense that it sees the world ‘out there’ as no more than a reflection of itself: the body becomes just the first thing we see out there, and we feel impelled to shape it to our sense of how it ‘should’ be. (Ibid, p48) which points to questions I have been asking. In the previous post, I wrote, “I have been reading Laurence Stern’s (2009;[1759]] The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman , which was written at a critical juncture within that making [of the Western world]. It is one of several potential connections, which seem to point to a general obsession with self in Western culture.”

But then McGilchrist thoroughly dismisses certain contemporary art, failing to see the artist’s role, not only as an observer and reporter but also as a conduit through which we might find ways to understand, question and explore the modern world and what he describes as its schizoid ontology. In the final section of his book, he titles a section “THE PROBLEM OF ART IN THE MODERN WORLD” (Ibid; 407). Don’t get me wrong, I think there is an awful lot to critique and question in contemporary art. I also side with his complaint, “Beauty is rarely mentioned in contemporary art critiques: in a reflection of the left hemisphere’s values, a work is now conventionally praised as ‘strong’ or ‘challenging’, in the rhetoric of power, the only rhetoric in all our relations with the world and with one another that we are now permitted” (Ibid: p.443). And I too have much to say about the anti-aesthetic, anti-photography, loser-images rhetoric that may come from a place of wanting to challenge dominant, commodified norms. But arguably, like most or all binary logic, it inadvertently underscores what it hopes to dismantle.

But here is where I start to become uncomfortable – and yes, I’m grown up to admit it is because his words challenge my strategies: “…metaphor and myth have been replaced by the symbolic, or worse, by a concept”. This seems unfair since myth is constantly being explored and re-explored in the contemporary art I explore and make. While he says a great deal valuable about art too, his view in the main seems unforgiving (Ibid; p442):

We stand or sit there solemnly contemplating the genius of the artwork, like the passive, well-behaved bourgeois that we are, when we should be calling someone’s bluff. My bet is that our age will be viewed in retrospect with amusement, as an age remarkable not only for its cynicism, but for its gullibility.”

A more nuanced argument is presented by Andrea Fraser (2006), which I have mentioned elsewhere.

Potential Connection Three: Nothing will come from nothing and movement

There is a great deal more to say, to be fair to both McGilchrsit and contemporary art, and it will take me a long time to make sense of McGilchrist’s words. In the meantime, I continue to connect Hayles’ (2017) ‘non-conscious cognition’, Sterne’s 1759 Tristram Shandy, and contemporary art strategies. Sterne’s book was loathed and loved and provides a precursor to surrealist tropes. It is very funny, pokes fun at itself constantly, and is reflexive, fragmented and non-linear. It is also unashamedly bawdy, often homoerotic (no, Uncle Toby is not merely too shy to know much about women), and teeming with double-entendre.

In the previous post, I shared Tristram’s image of a squiggle. One of my digital Big Others, Gemini, described the squiggle as exemplifying the following: 1. The tension between controlled representation and expressive impulse. 2. The subjective nature of interpretation and how we ascribe meaning.

While I read, I can’t help wondering what happened to the English psyche between the publication of Sterne’s book and the era of Oscar Wilde, famously ‘gaoled’ for his homosexuality, or later, when Turing was forced by society into therapy designed to ‘cure’ him’ while contributing to an early death. Not to mention the shameful lack of appreciation from society given his efforts in WWII. Although homosexuality is no longer illegal in the UK, hatred and bigotry persist here and around the globe, as does persecution. It’s as if society cannot stop yearning for stasis. We want fixed ideas of gender, sexuality, interior, exterior, and more. And yet, reality is not that. Whatever door you choose to enter to explore reality – physics, art, biology, ecology, philosophy – movement is an inescapable factor. This is not a metaphor. We live on a spinning globe, hurtling through space. The land we stand on never stops moving. Lines everywhere are constantly dissolving and reforming. Words too are emergent properties of matter, only accessible through matter, so why should they be any different? (They are not!)

This is brilliantly illustrated in an animation that shows how empty space is never empty, dead or still. And at the most fundamental level – so-called empty space – there is a LOT of movement. We are warned not to take quantum images literally at the macroscopic scale, however, I wrote the following in an essay, quoting Karen Barad (2007; p110), and I stand by it:

“Although we are used to thinking about quantum physics describing the very small and classical physics, the large, Barad (2007:337) urges us to consider how these “separate determinate boundaries and properties” are based on Western human habits of thought. Quantum and classical physics are different models that aim to describe how things work in the same universe – not separate realities” (Field, 2020, p39 citing Barad).

I recently discovered Thomas Nail’s philosophy of movement which furthers the notion that movement is everywhere and in everything. Nail (2018; p51) writes in his close reading of Lucretius;

“De Rerum Natura calls for nothing less than a wholesale overturning of Western philosophy with its statism, logocentrism, idealism, patriarchy, and heteronormativity […] To overturn religion, from the Latin words religione and religio, is to overturn the first and most basic misunderstanding of philosophy: that stasis comes before movement.” (My bold and italics).

These comments about movement apply to all reality, including the material realities that come in the form of historical concepts. These concepts are material in that they are usually accessed in books, digital devices, through films or some other medium. Even if we remove all those objects/processes and imagine we are hearing them aurally from an ancient storyteller before the invention of writing, the human telling the story is material. Material that eats, shits, loves, and dies. And material that is intertwined/enmeshed/assembled with the other materials in which all materials exist. There are arguments to suggest that we might remove the S and refer simply to material.

Potential Connection Four: Shifting lines around historical eras, including the one from which the modern Western world emerges

Shortly after reading Books One and Two on Sterne’s novel, the following article appeared in The Guardian demonstrating that lines, often arbitrary, carve up historical eras but are also not fixed.

“The Industrial Revolution started more than 100 years earlier than previously thought, new research suggests, with Britons already shifting from agricultural work to manufacturing in the 1600s.

Seventeenth century Britain can be understood as the start of the Industrial Revolution, laying down the foundations for a shift from an agricultural and crafts-based society to a manufacturing-dominated economy, in which networks of home-based artisans worked with merchants, functioning similarly to factories.”

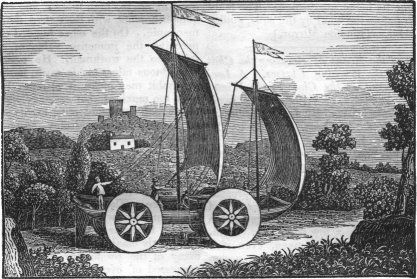

In Sterne’s fragmented narrative, there are plenty of comments on the Industrial Revolution and how burgeoning capitalist drives influence a human’s view. For instance, why asks Uncle Toby, do people who live on open plains like ours not make use of “Stevinus’ sailing chariot” when, unlike horses, they eat nothing and rely on wind for power, which costs nothing. Because, answers Uncle Toby’s brother and Tristram’s father, Walter Shandy, they eat nothing and cost nothing to power – “the scheme is bad. It is the consumption of our products, as well as the manufacturers of them, which gives bread to the hungry, circulates trade, – brings money, and supports the value of our lands; and tho’, I own, if I was a Prince, I would generously recompense the scientific head which bought forth such contrivances; yet I would as peremptorily suppress the use of them”. (2017 [1759], p.79-80)

Not only does this passage indicate how the same arguments are being played out today, it is also an example of time narrative, concepts and debate energetically crisscrossing spacetime. It also potentially supports The Guardian article which dissolves the fixed categorisations we impose on history. Of course, the Industrial Revolution did not suddenly appear out of a vacuum. And in any case, as we see above, a vacuum is never still or empty. It is always teeming with possibility and decay. For me, the specific changes and shifts in our historical narrative are less interesting than the fact that we’re questioning these lines at all.

Reality is not static. The whole idea of reality being static is a fantasy. We emerge into the universe for a moment and de-merge again soon afterwards. Is the obsession with self, which McGilchrist discusses, what prompts us to slow things down, even stop, fix, or shutter them? Do these attempts to control provide us with the illusion we are in charge? (And how does this relate to volition and free will? Well, that is the question, isn’t it?)

And so I come to the heading of this post. I am thinking about the words shutter, stop, and fix and photography. And wondering what on earth happened to make those 19th-century industrialists, perhaps some of the most suppressed people ever to be born on the planet, come up with a mechanical eye that functions by fixing, stopping and shutting reality down. (Incidentally, the camera too did not appear overnight. In fact, Shandy says the following: Others, to mend the matter, will make a drawing of you in the camera; that is most unfair of all, because there you are sure to be represented in some of your most ridiculous attitudes (Iid; p56). Referring, presumably to the camera-obscura).

Although this is not a new inquiry (and I explore the same through Barad’s agential realism lens while completing my BA (Field, 202), I suspect the answer is linked to the topic in The Guardian article, and in Walter Shandy’s response regarding the “consumption of products”.

Despite McGilchrist and others’ distaste for ‘I/it’ dialogue, I asked Claude and Grammerly to help identify what needs expanding in future writings. I find it helpful because, as he likes to point out, I am not a machine. But I also think the machine misses things…

And so, I end by promising a shorter blog next time!

Digital Big Other’s Feedback

Claude

- The reference to Laurence Stern’s “Tristram Shandy” and the parallels drawn between its fragmented, non-linear narrative and contemporary art strategies is insightful. The author could further explore how Sterne’s work presages surrealist techniques and challenges traditional modes of storytelling, which could be seen as precursors to the “anti-aesthetic, anti-photography, loser-images rhetoric” in contemporary art.

- The discussion of movement, stasis, and the dissolution of boundaries between disciplines and concepts is strong, particularly the connections made to Karen Barad’s work on quantum physics and Thomas Nail’s philosophy of movement. This could be expanded upon to more clearly illustrate how these ideas challenge the Western tendency towards “statism, logocentrism, idealism, patriarchy, and heteronormativity.”

- The juxtaposition of the Guardian article on the earlier-than-thought origins of the Industrial Revolution with the passage from “Tristram Shandy” is an effective way to demonstrate how historical narratives and categorizations are fluid and open to reinterpretation. The author could further develop this point by exploring how this fluidity and questioning of fixed boundaries relates to the broader themes of the text.

- The final section on photography and the author’s questioning of why the 19th-century industrialists developed a “mechanical eye” that “functions by fixing, stopping and shutting reality down” is intriguing. This could be expanded upon by connecting it more directly to the earlier discussions of movement, stasis, and the Western desire for control and fixity in the face of a fundamentally fluid reality.

Grammarly’s suggestions

What does the author mean by “modern world and its schizoid ontology”?

How does the author reconcile their appreciation for contemporary art with McGilchrist’s dismissal of it?

What is the connection between Hayles’ ‘non-conscious cognition’, Sterne’s 1759 Tristram Shandy, and contemporary art strategiess.

*A phrase from Achille Mbembe which I cannot go into here as this already far too long! But I will at some point.

Refs:

Ahmed, M. and Field, S.-J. (2024) In Pursuit of an Apparition, Hands Can Miss the Object [Zine]. Available at: https://www.sarahjanefield.com/products/in-pursuit-of-an-apparition-hands-can-miss-the-object (Accessed 12 April 2024)

Barad, K.M. (2007) Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Field, ~ Sarah-Jane (2020) ‘Image in the age of entanglement’, SJField – OCA Level Three Study Blog, 13 August. Available at: https://sjflevel3.photo.blog/2020/08/13/cs-a5-final-edit-of-essay-image-in-the-age-of-entanglement/ (Accessed: 12 December 2023).

Fraser, A. (2006) ‘Why Does Fred Sandback’s Work Make Me Cry?’, Grey Room, (22), pp. 30–47.

Hayles, N.K. (2017) Unthought: the power of the cognitive nonconscious. Chicago (Ill.): University of Chicago press.

Hall, R. (2024) ‘Industrial Revolution began in 17th not 18th century, say academics’, The Guardian, 4 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2024/apr/05/industrial-revolution-began-in-17th-not-18th-century-say-academics (Accessed: 8 April 2024).

Achille Mbembe: ‘Negative Messianism in the Age of Animism’ (2017). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyHUJYfk_os (Accessed: 24 May 2022).

McGilchrist, I. (2019) The master and his emissary: the divided brain and the making of the Western world. New expanded edition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Nail, T. (2018) Lucretius I: an ontology of motion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Sterne, L. (2017) The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, gentleman. Kindle Edition. Miami: Hardpress.